Press Release

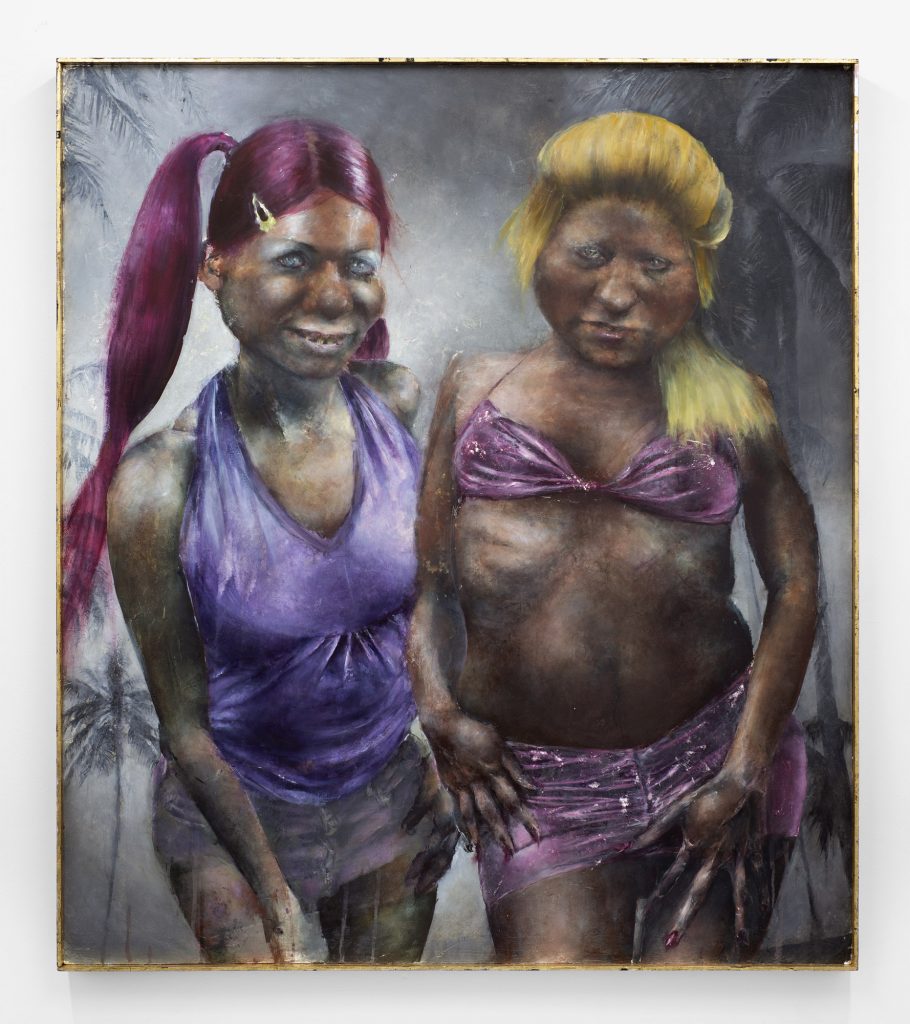

Catherine Mulligan treats the surfaces of her oil paintings with an artificial patina, as if the paintings themselves weathered the hostile conditions of her imagined hellscapes. The works that populate Vanitas—which span portraits of zombified women, banal web advertising graphics, and desolate, deindustrialized Rust Belt architecture—appear variously oxidized, corroded, and mildewed. Mulligan distorts color, but not form, with a sallow, polluted pallette. Even the undead women seem enervated by it. Their complexion is jaundiced; their bellies are distended; they have leathery, elastic skin and visible rib cages. They appear to be calcified—hardened by their encounter with an implied camera lens. On the other side of the lens, the abjected women make direct eye contact, neutralizing any attempt at voyeurism with glassy thousand-yard stares. Their posturing is contrived and awkward, not candid. These qualities bear a faint resemblance to the aesthetic rubric of fast fashion advertising, amateur modeling, and pornography that Mulligan often excavates images from. She doesn’t fabulate stories about these women, but they each have a plausible charisma. They make affective bargains with us, challenging us to conjure up some vague, pretended memory of them—as mid-naughts celebrities, maybe. They aren’t anonymous, but they exist somewhere even Mulligan can’t access. Her “monsters,” as she calls them, invoke the repressed cultural cachet of the early 2000s: they are decorated with SHEIN and Fashion Nova simulations of Y2K designs—copies of copies that have lost all specificity. For Mulligan, hell is the recent past.

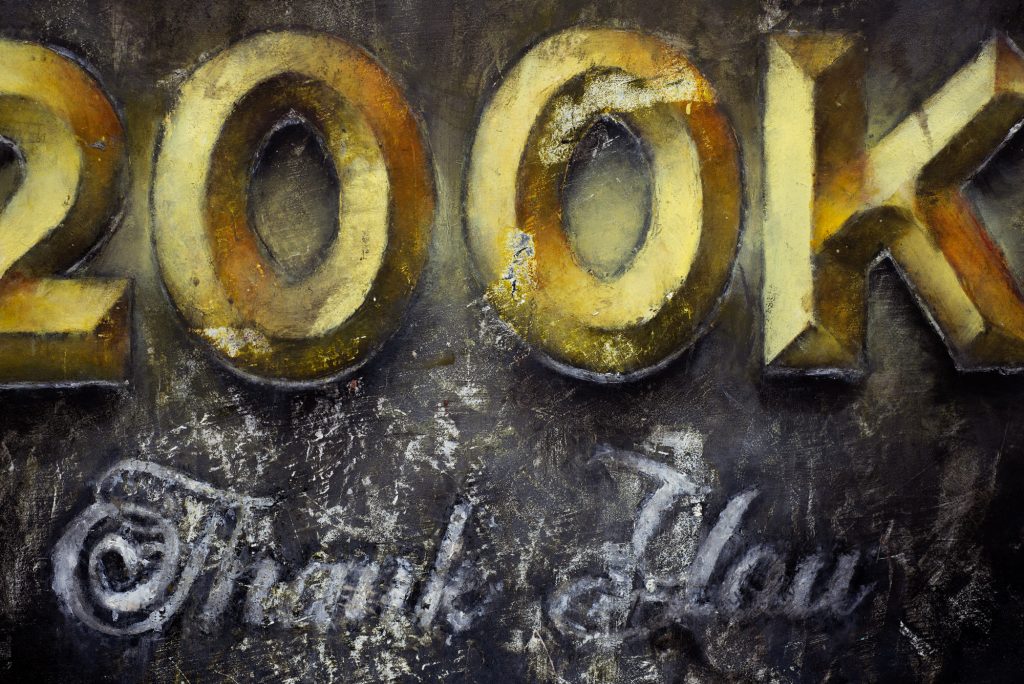

Mulligan gives the women, the graphics, and the buildings all similar treatments: each of them emerges, enfeebled, from a smoky miasma resembling a late ’90s Glamour Shots backdrop. Or perhaps she has captured their chemical sublimation from a solid to a gaseous state, dispersing into effluvia. Figure is, apparently, consubstantial with ground. This is especially true in Mulligan’s desiccated landscape, in which ominous, vacant buildings on the sprawling grounds of a church are held in abeyance, rendered inert by thick fog, bricked-over windows, and moldy, sun-bleached signage. It’s unclear whether this place occupies the same extended universe as the zombies, or if it is a portal to their world. Mulligan’s fictive vignettes are unspecific—she is careful not to overarticulate. Even so, her nightmare world is undeniably eschatological. 200K Thank You and FREE Links were once slick, high-gloss vector illustrations: something must have happened to them. It’s hard to say what, though, since “200K Thank You” and “FREE Links” have no specific referent. They are floating signifiers, unmoored from meaning. The promiscuity of this kitschy internet vernacular, which proliferates across pop-up ads, is the result of a deeply intertwingled internet infrastructure, à la Ted Nelson. Mulligan attends to these recently-vintage computer graphics with the interest of a media archaeologist, prompting us to consider what happens to the poor images that have obsolesced: what if, instead of pixelating away, they perished like organic matter? Digital media, of course, does not decompose organically. Instead, as Wendy Hui Kyong Chun has pointed out, it copies in order to save and erases in order to keep going. Mulligan pictures a perverse alternative to this cycle of disposal—one in which the stock graphic has the dignity of decay: it is disarticulated by bacteria and fungi, and eventually metabolized again by the world. Rather than a file, she manages it like an object, which can be rotted, not just corrupted. She imagines what it would look like to venerate the disposable, with a painterly strategy borrowed from religious paintings of the Northern Renaissance and Baroque periods. Mulligan putrefies in order to purify, like a historic Dutch vanitas. As its namesake in the Book of Ecclesiastes observes, “Vanity of vanities, saith the Preacher, vanity of vanities, all is vanity.”

—Amelia Farley

Catherine Mulligan (b. 1987, Nutley NJ) is a painter based in Brooklyn, NY. She has exhibited internationally, recently showing at A.D Gallery (NY), Gern en Regalia (NY) Hans Gallery (Chicago), Envy6011 (New Zealand), Downs & Ross (NYC), M+B (LA) and Harkawik (NYC), along with participating in the Bonner Kunstverein Jahresgaben in 2021. She is the recipient of two Elizabeth Greenshields Foundation grants. Mulligan earned her BFA from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (2009) and University of Pennsylvania (2010) and holds an MFA from Indiana University, Bloomington (2019).

Region

Location

-

373 Broadway, New York City, New York 10013, United States

Add a review